Now that I have the internet, some longer comments about Cushman's ratings thesis.

There's two things here. First, Cushman is admitting that the ratings numbers he reports for the first few weeks the series was on the air were later adjusted to include rural communities, decreasing Star Trek's share. We know this because the numbers Cushman prints for "Charlie X" and "Where No Man Has Gone Before" show it beating My Three Sons both times, but the revised numbers put the sitcom several ratings points ahead of Star Trek. Second, there's the matter of TVQ.

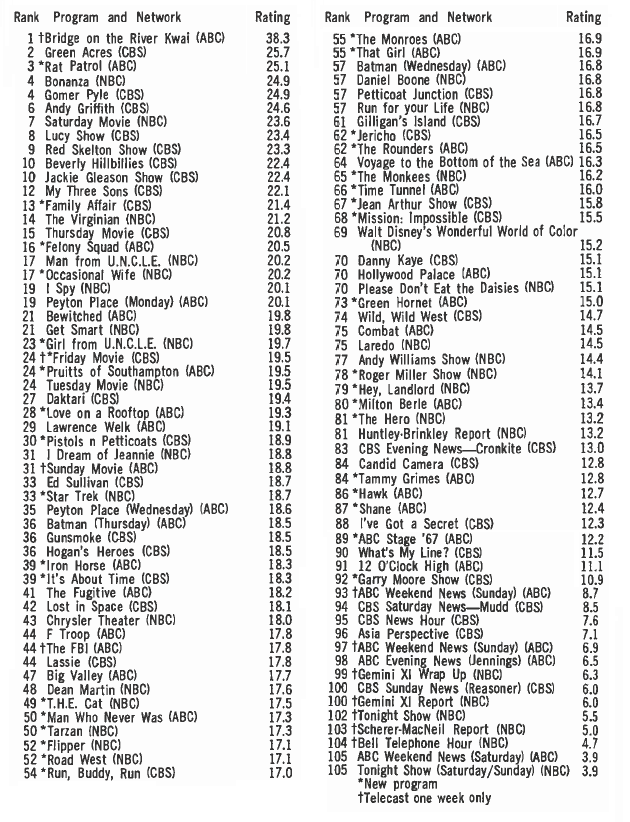

Cushman is right in as much as there was a TVQ survey that ranked Star Trek among the top ten series on TV in terms of TVQ, but his characterization of it as a nose counting service is a misrepresentation of what TVQ is actually measuring. Here's the TVQ report he's referencing (from Broadcasting, 12-5-66):

For a little detail on how TVQ is measured, I'll quote from Television Magazine (August 1967; note the part I've bolded):

EDIT:

Another part of Cushman's argument:

Some points to consider:

--Cushman considers Shatner's first season salary of $5,000 an episode to be chump change, but consider the fact that the cast of Bonanza, which was TV's number one drama going into the 66-67 season (its eighth) were "only" earning $12,000 an episode (after seven years of contractual raises, no less). $5,000 for an unproven television lead on an unproven series wasn't bad in the least.

--Cushman belief that the ratings were withheld from the producers (i.e. Roddenberry) holds up until you look at the files at UCLA, which include several ratings reports in Roddenberry's files.

--Cushman's belief that the ratings were secret in the '60s, but public now, doesn't stand up to much scrutiny. Then, as now, many ratings are published by various press outlets, but the detailed Nielsen ratings reports are still unavailable for public consumption.

That's it for tonight. More, perhaps, later.

These Are The Voyages said:As in past airings, Nielsen’s National survey, factoring in rural communities, gave Star Trek a couple of percentage points less than the “overnights” conducted only in metropolitan areas. But Nielsen wasn’t the only service counting noses.

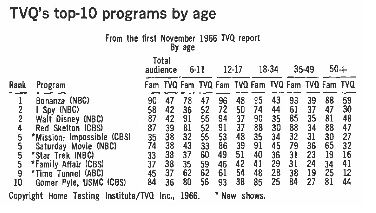

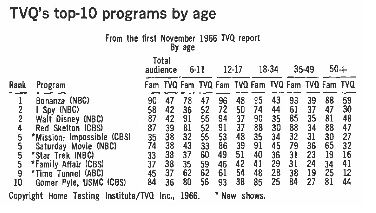

Home Testing Institute, A.C. Nielsen’s competitor, had a survey of its own called TVQ. For the month of October, which “Miri” closed out, TVQ prepared a Top 10 list and ranked Star Trek as being in a three-way tie for the fifth most popular series on TV, under Bonanza, I Spy, Walt Disney and Red Skelton, and tied with Mission: Impossible, Family Affair and the NBC Saturday Night Movie. The Time Tunnel and Gomer Pyle were at nine and ten, respectively.

There's two things here. First, Cushman is admitting that the ratings numbers he reports for the first few weeks the series was on the air were later adjusted to include rural communities, decreasing Star Trek's share. We know this because the numbers Cushman prints for "Charlie X" and "Where No Man Has Gone Before" show it beating My Three Sons both times, but the revised numbers put the sitcom several ratings points ahead of Star Trek. Second, there's the matter of TVQ.

Cushman is right in as much as there was a TVQ survey that ranked Star Trek among the top ten series on TV in terms of TVQ, but his characterization of it as a nose counting service is a misrepresentation of what TVQ is actually measuring. Here's the TVQ report he's referencing (from Broadcasting, 12-5-66):

For a little detail on how TVQ is measured, I'll quote from Television Magazine (August 1967; note the part I've bolded):

Another major grey-area yardstick for Klein is the “Q Number,” a service of TVQ. It is found by taking the number of people who consider a show among their favorites and dividing it by the total number of people who have seen the show. Thus a “high-Q show” has a dedicated following among people who have watched, although it may not have attracted a large audience.

Such a high-Q situation can occur when a good new show is put on the air against an established popular show; it may get a high-Q number as it picks up an interested audience from among those who tune in, while the majority of viewers are so busy watching their old favorite that they don’t soon get around to trying the high-Q show.

EDIT:

Another part of Cushman's argument:

These Are The Voyages said:In the 1960s, A.C. Nielsen delivered the gospel that the networks swore by. But there was an air of secrecy surrounding the gospels -- the ratings reports were not for public consumption. Nielsen would “loan” the survey documents to its customers -- NBC, CBS and ABC, who were very selective with whom the information was shared. Unlike today, those all-important life and death numbers for a television series were confidential. The theory was that if an actor, or producer for that matter, knew exactly how popular his show was, he would be all the more difficult to deal with. Time has proven this thinking correct. Consider how much more a star of a popular series is paid today compared to the 1960s. Shatner was a top-dollar star in 1966, but was only making $5,000 per episode. That would be comparable to around $35,000 now, a paycheck that most TV stars wouldn’t even get out of bed for. (Try a quarter of a million dollars per episode…or half a million…or, in some special cases, a cool million.) Somewhere along the line the stars and their agents got smart, and the networks and the studios lost control. In Star Trek’s day, however, the power was still held in check by the networks, and NBC was not about to share it with Gene Roddenberry.

Some points to consider:

--Cushman considers Shatner's first season salary of $5,000 an episode to be chump change, but consider the fact that the cast of Bonanza, which was TV's number one drama going into the 66-67 season (its eighth) were "only" earning $12,000 an episode (after seven years of contractual raises, no less). $5,000 for an unproven television lead on an unproven series wasn't bad in the least.

--Cushman belief that the ratings were withheld from the producers (i.e. Roddenberry) holds up until you look at the files at UCLA, which include several ratings reports in Roddenberry's files.

--Cushman's belief that the ratings were secret in the '60s, but public now, doesn't stand up to much scrutiny. Then, as now, many ratings are published by various press outlets, but the detailed Nielsen ratings reports are still unavailable for public consumption.

That's it for tonight. More, perhaps, later.

Last edited:

moments than the first volume as well. I never knew there were so many almost-cancelled moments during season two, but the timeline makes a lot of sense -- initial order of 16 episodes, after which Coon left, a mini-order of 2 more, followed by a final pick-up of the "back 8" while filming was underway for the 18th episode. Yeah, NBC was letting Star Trek twist in the wind there.

moments than the first volume as well. I never knew there were so many almost-cancelled moments during season two, but the timeline makes a lot of sense -- initial order of 16 episodes, after which Coon left, a mini-order of 2 more, followed by a final pick-up of the "back 8" while filming was underway for the 18th episode. Yeah, NBC was letting Star Trek twist in the wind there.