In the eagerness to slay some straw men, some curious claims have been made.

"Not at all. You use characters like George Washington or Lizzie Borden because everybody knows who they are and they carry all sort of evocative symbolic weight and associations. If I write a book in which Harry Houdini teams up with H. P. Lovecraft to fight Rasputin, who is actually an evil android from another dimension, I'm not making any claims about reality. I'm just having outrageous fun with famous, archetypal figures. It's all about imagination and fantasy . . . and, yes, silliness.

Which can be a blast, if you're not hung up on what is "serious" and "real" and constitutes "good" science fiction."

But the evocative symbolic weight and associations come from reality. Strictly speaking, real people are not archetypes. Insofar as they become archetypes, this is often propagandistic in orgin and function. Repeating stereotype really is not just good clean fun. Even when it's relatively benigh, it's not very original.

Again this is exactly the same as claiming that if you drop some scientific gobbledygook to justfiy outrageous fun, you're not actually expecting that, on some level, willing suspension of disbelief that such things don't really happen. Science fiction is not all about imagination and fantasy and silliness. Serious is not a synonym for solemn or pompous despite the misapprehensions of some of the dark & gritty school of hacks. The thing about good science fiction is that it has a peculiar kind of relevance to us, which does not come from outrageous fun.

""Make a claim about reality?" Of course not. Historical figures aren't just people who actually lived; they're symbols. Heck, many of them are myths in their own right. Most of what Americans believe about Christopher Columbus and much of what they believe about George Washington is pure fiction, fabricated by Washington Irving to give America a foundational mythology. So using a historical figure in a fantasy story isn't done in order to "claim" a damn thing about the real figure; it's done in order to invoke the symbolism and mythology surrounding that figure and use it as an element in an imaginary narrative.

The purpose of fiction isn't to "make a claim about" anything, unless it's specifically a polemic. The purpose of fiction is to tell satisfying stories, to entertain, stimulate, and enrich the audience. Any "claims" it makes are only meant to apply to the imaginary reality of the story, not to the external reality of the audience."

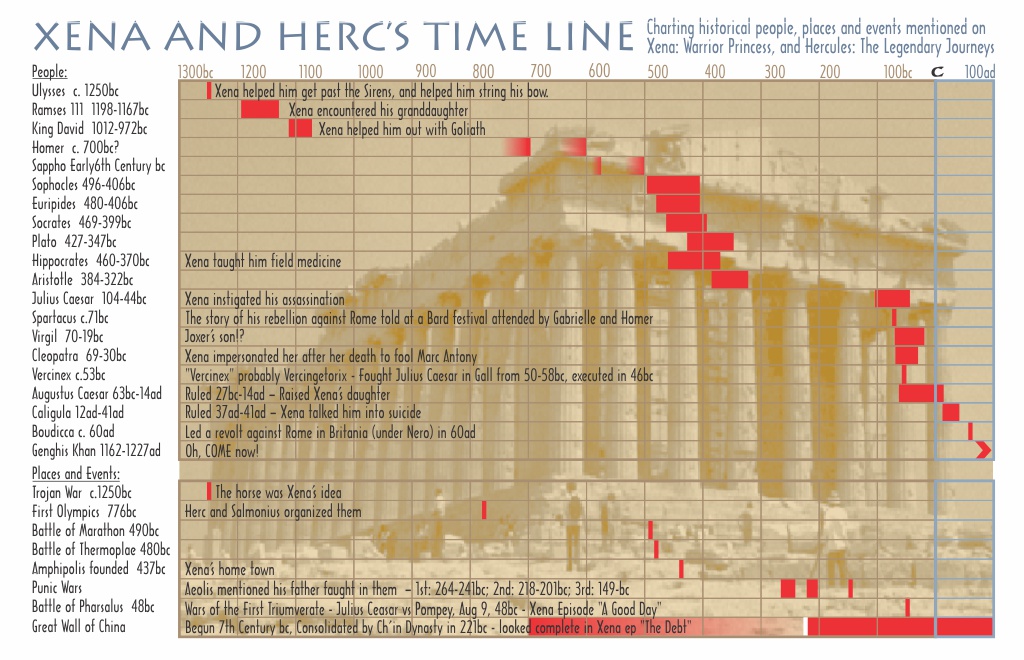

There is no compelling logic for preferring fantasy history over real history. That's why it's perfectly sensible to find Hercules and Xena's nonsense distasteful. In any event, preferring archetypes to real characters, even the simple point of view characters often found in SF, is a pretty extreme position. It is rooted in a desire to avoid saying anything serious.

The absurdity of saying that only polemical fiction makes claims about reality unfortunately seems to cover up a deeper, much uglier notion: Fiction and drama are not to criticize reality. Even at the price of enlisting fantasy history and fantasy science as a backdrop for the antics of archetypes, instead of people! Again, taking things seriously does not require solemnity and pomposity. But, taking things frivolously is much easier if you prefer fantasy to reality.

Despite all the outrage, the whole point is that the ludicrous historical archetypes lurching around Hercules and Xena are not really satsifying, not very stimulating, not only not enriching but on one level impoverishing. That only leaves entertaining. Devoid of other virtues, so often this kind of stuff boils down to, do I like Kevin Sorbo? Or does Lucy Lawless make me horny?

I don't think much of the entertainment standard. My guess is that cheap whores have been more "entertaining" than the best writers and dramatists.

PS About Braveheart: The movie was aimed at a population who mostly don't even know Scotland is not the same as England. This is a country where even finding a history of Scotland, much less biographies of the principals, is difficult, even in public libraries. So difficult in fact, that I could not list the distortions. The point seems to be that blatant historical falsification is irrelevant to entertainment. My original point was that blatant historical falsification tends to lapse into farce (supposedly a farce on historical truth in the case of Braveheart.) The need to argue that historical truth is undesirable because it's less entertaining is actually a pretty extreme opinion. It seems to me to be a form of obscurantism.