Well the fact that some dinosaurs HAD feathers kinda shows evidence that birds came from Dinos.

Interesting comment.

I found these two links that touch on this. Apparently there has been a bit of disagreement on which came first - feathers or scales.

http://www.dinosauria.com/jdp/archie/scutes.htm

Excerpt from the above link:

And there is also this site http://www.scribd.com/doc/7175181/FeducciaJMorph266200542Unfortunately, this evidence can also support the theory of many ornithologists that birds share a common ancestor with the dinosaurs, rather than descend directly from the dinosaurs (thus making the birds the fourth group of the archosauria). If feathers are primitive for the group as a whole, there is no inherent reason to think birds had to descend from dinosaurs.

The debate on the subject of bird origins will continue, with ornithologists and dinosaurologists continuing to argue the significance of shared characters. However, this debate will include one new factor, the similarity of dinosaur feathers to bird feathers. Should the feathers of Sinosauropteryx prove to be very close to the down of birds, it may at last bring the doubters of the dinosaurian ancestry of birds into the fold.

The experiments of Zou and Niswander, and Alan Brush, suggest that scutes evolved from feathers. Although the research does not provide hints as to the origin of feathers, it does remove the impediment to the dinosaur-bird theory by showing that while feathers probably did not evolve from scales, scutes, a character shared by dinosaurs, may have evolved from feathers. Recent finds suggest, if not outright prove, that dinosaurs had feathers. Whether feathers are primitive characteristics of the archosaurs is a question that will continue to fuel the debate of whether birds are dinosaurs or a sister group to the dinosaurs. However, the results of the research of Brush and Zou and Niswander, and new finds such as the feathered dinosaur Sinosauropteryx, help strengthen the relationship between dinosaurs and birds.

Excerpt:

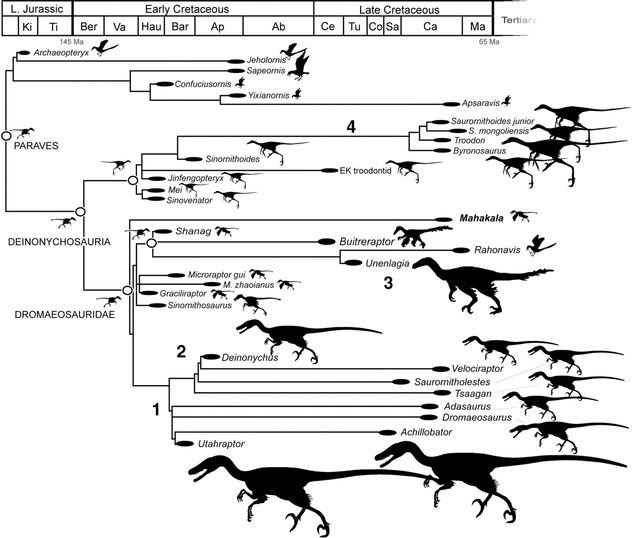

ABSTRACT The origin of birds and avian flight from within the archosaurian radiation has been among the most contentious issues in paleobiology. Although there is general agreement that birds are related to theropod dinosaurs at some level, debate centers on whether birds are derived directly from highly derived theropods, the current dogma, or from an earlier common ancestor lacking suites of derived anatomical characters. Recent discoveries from the Early Cretaceous of China have highlighted the debate, with claims of the discovery of all stages of feather evolution and ancestral birds (theropod dinosaurs), although the deposits are at least 25 million years younger than those containing the earliest known bird Archaeopteryx.

The frequently used phrase “birds are living dinosaurs” does little more than dampen research, because if it were true, then any fossil specimen with feathers in the Mesozoic would automatically be both a bird and a dinosaur. With the recent spectacular discovery of bird-like fossil footprints with a clearly preserved hallux from the Late Triassic (Melchor et al., 2002), Zhonghe Zhou (2004, p. 463) correctly notes, “it is probably too early to declare that ’it is time to abandon debate on the theropod origin of birds’ (Prum, 2002). Abandoning debate may succeed in concealing problems rather than finding solutions to important scientific questions.” The problem of avian origins is far from being resolved.