"Blue spill" can happen in a variety of ways—not just when the model is "too close" to the background. First, one must understand what bluescreening is all about.

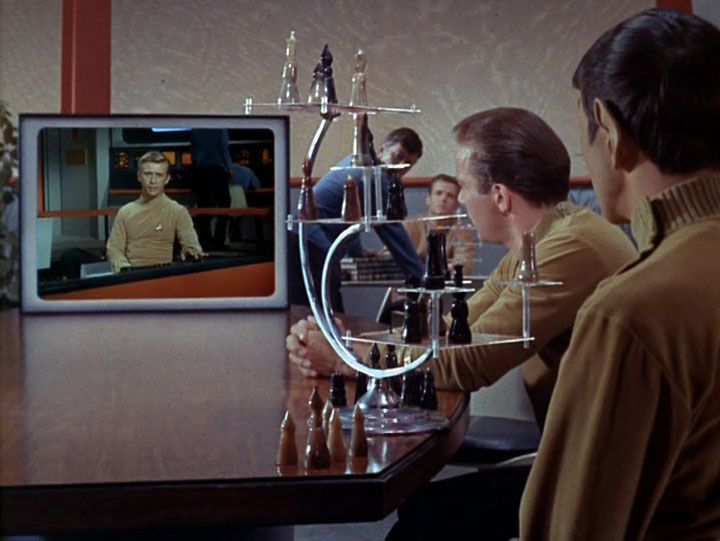

If one tries to make a composite shot, like the above shot of the

Enterprise in front of a planet, by taking a double exposure, then then the two will be seen through each other, like ghosts. However, if one can "cut out" the

Enterprise and stick it in front of the planet, the two won't show through each other. Masks to control this sort of exposure are called "mattes." When the mattes move, it is called a traveling matte. The oldest way of creating traveling mattes is with

rotoscope, a manual technique named after a device invented by animator Max Fleischer.

Bluescreen is just one of perhaps hundreds of different "automatic" traveling matte techniques invented by filmmakers. Bluescreen became popular because it would be done with common film stock, and did not require any special lights, film stocks, or other exotic materials.

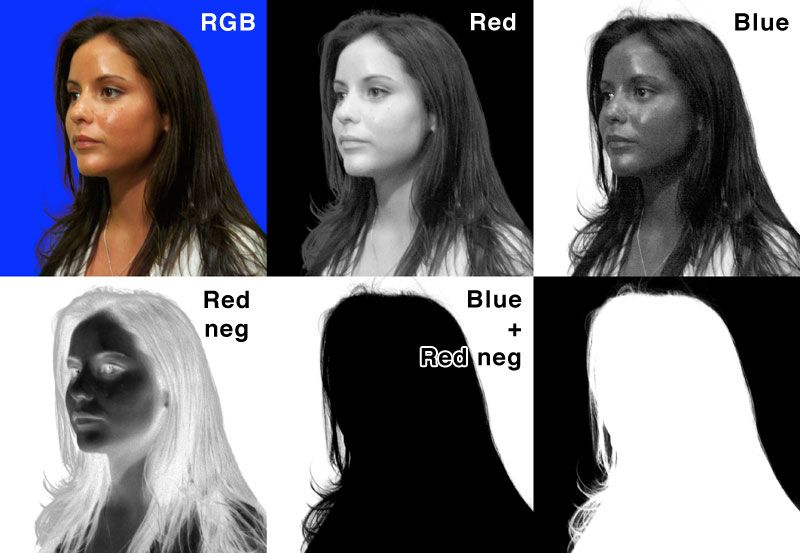

Bluescreen works on the very simple idea that blue things look dark through a red filter, and red things look dark through a blue filter. Take note of the blue background in the red and blue plates (top row) in the image below.

Now take note of what happens when the red plate is turned into a negative: the background becomes "white." Since the foreground subject is dark and light in opposite areas from the blue plate, placing the two plates on top of each other (called "bi-packing") results in the silhouette in the middle frame. This is one half of the matte.

Since film is clear where it appears white in this example, light will pass through. To create the composite, the black-on-white matte is bi-packed with the background and rephotographed. The film is rewound (without developing) and run for another pass, this time with the white-on-black matte bi-packed with the foreground subject. When the film is developed, one has a composite shot with no ghosting.

Of course, it's easier said than done. Bluescreen composites can suffer from a number of artifacts, like matte lines, "jigsawing" and other alignment problems. I won't go into detail about all of that here. In a pre-digital age, good mattes were a combination of art and science.

The "bite" taken out of the

Enterprise's warp engine (top) resulted from some form of "spill light." Light might have bounced off the studio floor and shone on the darker underside of the model. One can try to control spill with additional white lights, or lights with a faintly orange filter in them, but then the model appears to glow, as it has no actual shadows. "Spill" might also result from "specularity," as 3D modelers call it. Take note of the composite below. The table has a shiny finish, which allows us to see the white screen as it appeared on the set.

(The DP should have used a black screen. Then, budget permitting, the compositor could have exposed the "video" image inverted and blurred out on the table to make it look like a reflection.)

If even a little blue appeared on the

Enterprise model, the lab tech would have a hard time extracting a clean matte. The solid black mattes of the woman shown above (last two frames) were printed on "litho" film, which is absolute black or white. (Black areas on color film are actually semi-transparent, and thus no good for mattes.) Any gray areas would cut to either black or white, or produce speckly noise—like the bite taken out of the warp engine.

Today's compositors, working with digital tools, have the ultimate in control. I've gabbed too long already, so I won't go into digital tools. However, if you want to know how the old-timers did it (pardon the pun), I highly recommend

THE TECHNIQUE OF SPECIAL EFFECTS CINEMATOGRAPHY by Raymond Fielding, Focal Press. The book is available in print and ebook format.