Heritage

“You must go with me to Lakat,” Glinn Jelar said.

Jelar, an architect, ignored his brother’s words. Instead, he grabbed his brother’s arm and pulled him to the window.

“Is this your new Hebitia?” he hissed furiously.

He didn’t want to look at the burning city himself, so he focused on his twin brother’s face.

Glinn Jelar unemotionally looked out the window. “We have to be reborn if we are to survive,” he answered coldly.

“I’m not a farmer, but even I know that if you burn land nothing will grow on it later!” Jelar shouted and turned away from the window to enter deeper into the room, away from the view.

“Oh, you’re exaggerating! We don’t burn the whole city. If we were, I wouldn’t be in this building and neither would you!”

“No, you’re just burning temples. And tell me, how can you know if the fire wouldn’t catch the rest of the city,” he didn’t speak only metaphorically.

“What do you want us to do!” the glinn lost his patience. “When was the last time that a child died in your arms?!”

Jelar had nothing to say. He knew his brother was helping in relocating people from most affected regions, but the glinn never told him about children dying in his arms.

Glinn Jelar stared at his twin’s back for a moment.

“Tris,” he started, “I don’t want to argue with you. This is something we have to do. It’s not going to be easy, it’s not going to be nice, for some it’s going to be really ugly, but it has to be done. Or we’ll all die. There’s not enough food, some parts of the planet are inhabitable and we can’t tell when they would be safe again.”

“Of course you think that the asteroid and the moon were Oralians’ fault too,” Jelar muttered with irony.

“Oh, come on!” the glinn threw his arms up and then brought them down. His palms slapped armour plates on his hips.

“What! What do you expect me to say!”

“Sit down.” The glinn’s voice was soft and calm.

“No.”

“Sit down. Let’s talk.”

“I have nothing to say to you,” Jelar barked.

“I think you have a lot to say, you just don’t want to listen.”

Jelar turned and looked at the glinn. He then went to the only table in the room and sat at it. “Speak.” The word sounded like a command, not complying.

Glinn Jelar followed his brother and sat too, his brown-and-black armour squeaking quietly.

“Tell me, how did you feel when your best friend told you that you surely were an evil person because Oralius was not present in your life?” he asked.

“Betrayed.” Jelar’s eyes went to his hands; his voice was so quiet when he said that word that the glinn could barely hear him. Glinn Jelar’s heart ached—he remembered all too well how hurt his brother had been. They had been only eleven years old and hadn’t understand much of how the world worked but that they had understood really well. Glinn Jelar had wanted to beat that so-called friend after school but he had decided against it. It would only prove that asshole’s point of view and his point of view was wrong.

“And why did we hide from the other children the fact that we weren’t going to praying services twice a week, every week? Why did we lie that we were going to another temple?”

“Because we were afraid to admit that we were not Oralians. You know all that.” Jelar didn’t raise his head.

“This is going to change. Children shouldn’t be afraid to admit that they are non-believers. No one is going to judge you based on your going or not going to a temple every naiyat and sapyat. People should be judged by their actions, not by their attendance to a temple.”

“And what your actions tell about you?” Jelar raised his head and looked at the glinn with his big, shiny eyes. “One kid was nasty to me years ago and you want to kill them all for that?”

“Do you really think you were such unique a case? And we don’t kill them.”

“Mhm,” Jelar’s throat emitted. “I’m sure they appreciate that,” he said with irony.

“Would you prefer if nothing changed?”

“No. But I don’t like the way you do this. A man from a colony comes and tells you to destroy your soul. And you do it! Why?”

“Soul?” The glinn’s eye ridges arched a little.

“We may not be Oralians, but we still are Hebitians. And their history is also ours. If you burn all books and all historic buildings, all you’re going to have is emptiness. Nothing. Vacuum.”

“We can fill it with new books and new buildings.”

“You can’t go on without a past. We have our rich culture. You are trying to destroy it. To erase it. To undo it. Do you think it would turn back time or send that asteroid away from our moon? It had happened and you can’t do anything about it.”

“I see. So if we don’t proceed and don’t reform our world, we will stop dying, starving, freezing or overheating. Is that what you’re saying?”

“No.”

“Good. Because I started to think my own brother is an idiot.” He silenced for a moment. “We lost our moon. What’s worse, it split after being hit and huge chunks hit us and killed many people. Change in the tilt of our planet brought changes in our climate. That caused melting snow on both poles. And that cause raising see level. And that caused shrinking living space. And that caused...the list goes on and you know it.” He took a deep breath. “We have to adapt. But they refused to adapt. Some of them claim that it was Oralius’s punishment for existence of people like you and me.” He shook his head in disbelief.

“They are extremists and you know that. Other factions rejected to accept such an explanation.”

“But they didn’t propose much more than a prayer. We, however, went to the affected areas with food, medicine and help. We help them to move to safer places. For you or me the Great Collision happened twelve years ago. For people living in those regions—yesterday, because for them very little changed since day one. Their guides made a ruling to pray three times a week instead of two. We brought them clean water and blankets.”

“And that’s why you have to set historic buildings on fire?”

“We have to clean.”

“Would you also ‘clean’ Uncle Ratak?” Jelar raised his voice.

Glinn Jelar didn’t answer.

“Look, Zori, I understand we need to do something. I know the last three winters were terrible and we have less and less food. The raise in temperature seems to be permanent and the pollution difficult to fight, but I don’t see how rejecting our cultural legacy could help in fixing all that. Who are we going to be when we stop being Hebitians?” His face expressed sadness and worry.

“Cardassians.” The answer was short and firm. Was there pride in the glinn’s voice or did Jelar imagine that?

He blinked. “What?”

“Assiya gives us light and warmth. Cardiya is no more, destroyed by that asteroid, but it cannot be forgotten. Both stellar bodies were important for this planet and Akleen believes it should be reflected in the planet’s name. Cardassia. And it makes us—the Cardassians. The Hebitians are dead. Hebitia failed. Cardassia will unify all of our people everywhere and thrive.”

Jelar wouldn’t admit it to his twin brother but he liked it. He really did. But... “Does it mean you have to destroy everything Hebitian?”

“We need to start from the beginning. To build everything from the scratch. Nothing should link us to this...failure.” The glinn waved toward the window and burning city beyond it. Then he looked at his brother and put his hand on Jelar’s. “Tris, you have to support us.”

“But I don’t agree with what you’re doing.”

“You know it’s for the best.”

“How could I know?” he pulled his hand away from this brother’s and put it between his body and upper arm, as if hiding it. “First you burn books, then buildings, in the end you’ll burn people!”

“How dare you!” The glinn started from his chair, knocking it over.

“Zori, can’t you see? This is wrong.”

Glinn Jelar only shook his head. “Do you really want guides to keep ruling us? Do you want them to create law that outlaws people who don’t share their religion? Do you want us to be governed by people who believe laughter is wrong? Happiness is a sin?”

“Not all guides are like this,” Jelar shook his head. “Merely two days ago I talked to one from Nokar. Used to our grim and deadly serious guides I asked her why she was so cheerful. Do you know what she’s told me? It was her mission to be cheerful. It was her job. Her duty. How could she support her faction, how could she advise her people, how could she be a guide if she were sad and gloomy.”

The glinn gave him a look of disbelief. “Seriously?” His voice had a high pitch of surprise.

“She didn’t stop smiling even for a second when we talked.”

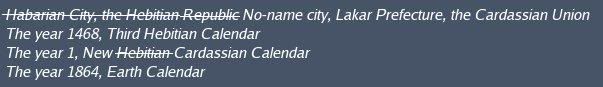

Glinn Jelar picked the chair up and put it straight, then sat on it. He didn’t say anything for a long moment. The minutes dragged and the silence grew heavy. Finally, the glinn started to speak, quietly, his tone of voice pleading. “Tris, please go with me to Lakat. We must leave Habarian City and Lakar Prefecture.” He used the new name of the administration unit of the province. “You must go with me. And you mustn’t talk to anyone about your siding with Oralians.”

“I’m not siding with anyone. I try to be neutral.”

“You’re not from where I’m standing.”

“What kind of philosophy is that? ‘You’re either with us or against us’?”

“We cannot allow any remains of old Hebitia to stay here. It must be eradicated.”

“Why?”

“Because we don’t want to repeat their mistakes.”

“And how would you know what those mistakes were if you delete the history from your memory? There would be no examples to learn from.”

Glinn Jelar had to admit that his brother had a point. “At least we won’t prosecute people for not believing in Oralius.”

“And what will you prosecute people for?”

The glinn pursed his lips, then said, “You will go with me to Lakat.”

“And what are we going to do in that village? There’s nothing there.”

“No, not yet. We need you there, though.”

“I’m an architect, not a farmer.”

“Lakat may be a mere village, but I proposed you as one of planners in the team of people whose task is to design and build our new capitol there.”

Jelar was speechless. “Really?” he asked quietly.

“Really,” his twin brother answered with a grin. “So now you see that you have to go with me. You must change that village into a city, a beautiful city, where the command would reside, where the central point of our new empire will be.”

Jelar’s eyes brightened and shone with excitement, but then they went to the window and the light in them dimmed. “And this?”

“And this will be buried, forgotten and unimportant.”

“I can’t,” he shook his head. “I can’t. My conscience wouldn’t let me sleep.”

“Tris, please...” Glinn Jelar leaned toward his brother over the table, his armour squeaked as it pressed to the edge of the table top. The other twin kept shaking his head. “Please, I’m begging you.” Tears appeared in the glinn’s eyes. “Do it for me. Do it for my conscience.”

“For your--” Jelar was clearly puzzled. “For your conscience? What do you have to do with it?”

“Just do it for me.”

Shaking head again. Jelar expected his brother to get angry, but the glinn was only more worried.

Suddenly the door opened and three armoured men entered. One of them, a glinn, looked at Glinn Jelar.

“Did he agree?” he asked.

“Not yet, but--”

The nameless glinn motioned to the other two—both with a rank of garesh—and they approached Jelar and grabbed him by upper arms and forced him to stand up.

“No!” Glinn Jelar shouted, running to his brother. “Let him go! I will convince him. I just need more time.”

“You ran out of time. He has been expressing anti-revolutionary views. He is too dangerous.”

“No!” Glinn Jelar started toward the glinn but the soldier quickly retrieved his weapon and pointed at Glinn Jelar’s face.

“I hope you are proud of your revolution,” Jelar whispered. His twin brother turned to look at him, ignoring the business end of the gun at his face, and opened his mouth to say something but he found no words to say.

“Take him,” the nameless glinn barked. Jelar didn’t resist, he let the soldiers to take him out. “I’ll be watching you,” the glinn said to the other brother and then lowered his weapon. “I’ll be watching you very carefully.”

Glinn Jelar didn’t hear him. He listened to the steps of three men on the corridor. He wanted to follow them but his legs were frozen, rooted to the floor. He looked at the window and immediately looked away from it. He knew they would take him to the street and do it there. He would not dare to look at the window now. He would not dare to approach it and look outside, to the street below. He didn’t have too. He knew all too well what it would be like. All he had to do was to close his eyes to see it. And he knew it would haunt him for the rest of his life.

The end