-

Welcome! The TrekBBS is the number one place to chat about Star Trek with like-minded fans.

If you are not already a member then please register an account and join in the discussion!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Help -- Going from PC to Mac

- Thread starter John Picard

- Start date

Leopard. Panther was 10.3. I'm using Leopard now with no particular issues, but it's still pretty new to me; I stuck with Tiger for a *long* time.

Yeah, 10.3 is what I meant. Sorry about the mix-up. I'm a little distracted with things right now.

Panther wasn't the best OS ever. I don't recall the specific issues, but while 10.2 was a big step over 10.1, I don't recall really being satisfied with an OS after that until 10.4. I wish it were easier to recall specifics....

-and-

I've had the opportunity to work with most of the operating systems in the developmental history of Mac OS X (including many which were never released to the general public). The one trait that all of these operating systems have in common is stability. If run on the proper hardware, all of these operating systems have been very stable. Now just saying that I've used them isn't really enough to drive the point home here, so here is a list of the ones I have had extensive experience using:I did get the impression that 10.3 was a bit of a lemon.

- NEXTSTEP 2.0

- NEXTSTEP 2.1

- NEXTSTEP 3.1

- NEXTSTEP 3.2

- NEXTSTEP 3.3

- OPENSTEP 4.1

- OPENSTEP 4.2

- Rhapsody 5.0 (Rhapsody Developer Release)

- Rhapsody 5.1 (Rhapsody Developer Release 2)

- Rhapsody 5.3-5.5 (Mac OS X Server 1.0.x)

- Rhapsody 5.6 (Mac OS X Server 1.2 & 1.2v3)

- Mac OS X Developer Preview 3

- Mac OS X Developer Preview 4

- Mac OS X Public Beta

- Mac OS X v10.0.x

- Mac OS X v10.1.x

- Mac OS X v10.2.x

- Mac OS X v10.3.x

- Mac OS X v10.4.x

- Mac OS X v10.5.x

Were there ones that I wouldn't use to aid me in getting work done? Absolutely, which is why there are gaps between some of the releases I still currently use on that list. But none of those gaps are due to the base OS, but rather changes happening to the application environment. An operating system is, after all, only as good as the applications which can be run on it. And the best operating system in the world without applications is really pretty useless.

Some of the transitions were harder (and longer) than others. The move from NEXTSTEP to OPENSTEP was relatively painless, but that was because both Sun and NeXT spent a good deal of time making sure to not damage what worked while creating the OpenStep Specifications, and then not removing backwards compatibility while applying those specifications to OPENSTEP 4.x.

The move from OPENSTEP to Rhapsody was more painful because not only was backwards compatibility lost, the foundations for applications were expanded and the interface was changed. So while the first version of Rhapsody may have been rock solid, it was also nearly as useful as a rock. While missing some of the refinements of later versions, the next version of Rhapsody was a very usable operating system (which I have been using consistently on an IBM ThinkPad since 1999 for actual work), and this was mainly because it was a good environment for running good applications (which I happen to have quite a few). By the final release of Rhapsody (then called Mac OS X Server 1.2v3) in 2000, the environment had become a great place to do work in and developers had put together some great applications for it. I have two systems (a Power Macintosh 8600/300 and a PowerBook G3/300) that are still running this operating system today.

But neither of those transitions faced the daunting task of moving from Rhapsody to Mac OS X. I had (and was giving Apple feedback on) many of the early versions of Mac OS X... but I sure wasn't using them to get any work done (my Rhapsody and Mac OS 8/9 systems were where I was doing my actual computing). That transition had some massive hurdles to overcome.

First of these was removing all the 4.4BSD (encumbered) elements and replacing them with elements from 4.4BSD Lite, FreeBSD, NetBSD and OpenBSD. This created Darwin and meant that Apple would no longer have to pay the Regents of the University of California for every copy of the operating system sold (based on the license agreement that NeXT had entered into in the late 1980s). That part was actually relatively painless and didn't have a major impact on the user environment (the first Mac OS X Developer Preview seemed almost identical to the concurrently shipping Rhapsody based Mac OS X Server 1.0.x).

The next wasn't so easy. Back in the days of Apple's Copland project, developers told Apple in no uncertain terms that they would not do extensive rewrites of their applications for a new Apple operating system. It didn't matter if those applications would benefit from the new operating system, they couldn't justify the time and effort. When the developers (like Adobe, Microsoft and Macromedia) took the same stand with Rhapsody, it caught a lot of people at Apple (who had come from NeXT) by surprise. The solution was to use what had been started in the Copland project in Rhapsody, and this was later called Carbon. Within the span of a few weeks Apple graft a version of Carbon into Rhapsody 5.1, they ported AppleWorks 5 and the lead Photoshop developer at Adobe ported Photoshop 5.0 and displayed those apps running as native applications in Rhapsody at WWDC 98. Even with those successful examples, Carbon wasn't ready. So Apple started developers off by including Carbon support in Mac OS 8.5 and continued to refine the Mac OS X version.

What a lot of people don't generally know is that developers were afraid that Carbon applications were going to be second class citizens in the new operating system. To prove it's commitment to Carbon, Apple made the most important application on the Mac in Carbon... the Finder. This wasn't a port of the Finder from Mac OS 8/9, this was a ground up new application which actually help refine Carbon. But at the same time made Mac OS X feel slower than previous versions in those early days.

At about the same time Apple realized that they could save more money by removing more of the licensed elements from the old NeXT days. NEXTSTEP, OPENSTEP and Rhapsody all used Display Postscript. Display Postscript was codeveloped by NeXT and Adobe, but NeXT and Apple still had to pay a license fee for every copy of the operating system sold. Apple replaced it with Display PDF (part of Apple's Quartz graphics). Between not having the level of refinement that Display Postscript had and the Mac OS X interface developers putting transparencies all over the place, this added another level of burden to Mac OS X.

Because most of the developers who made the applications I used in Rhapsody were making versions of these same applications for Mac OS X, I could use it early on to a reasonable degree... but there wasn't a good reason to stop using (or move any of my activities) from Rhapsody to Mac OS X back then. But what I had been hoping for was more of a replacement for Mac OS 8/9. My main Mac OS 8/9 applications run great in Rhapsody's Blue Box environment (and I still do that with many today), but having many of these apps running native together would have been great (and what I was wanting from Mac OS X). High on that list of apps was Photoshop.

As I pointed out earlier, one person at Adobe had ported Photoshop 5.0 to Carbon in Rhapsody within a few weeks back in 1998. One would think that Photoshop would have been the first Mac OS X native application by Adobe. It wasn't. Adobe ported Acrobat, Illustrator, InDesign, Premiere, AfterEffects, GoLive and LiveMotion to Mac OS X before Photoshop. Photoshop for Mac OS X was released at about the same time as Mac OS X v10.2. It seems that Adobe wasn't very happy about Apple replacing Display Postscript in Mac OS X (which would have been a nice source of revenue for Adobe), and holding back Photoshop was Adobe's way of punishing Apple.

So Mac OS X v10.2 was the first version of Mac OS X that I used for regular productive computing, and I still make use of it today (and it feels less cluttered than later versions to me). And the only reason I use 10.3 and 10.4 (and eventually 10.5) is application compatibility. The operating system itself (which I feel should do it's job well and otherwise stay out of the way) was pretty much finished for me in 10.2.

This isn't to say that there aren't great advances in later versions. One of the major philosophies from NeXT was that applications shouldn't have to reinvent the wheel for many elements. Why (for example) should each application have it's own spellchecking engine and database? Why not have one that all applications can use. And if one application does something well, why not share that ability with other applications. This is the concept behind services (I've written about this in the NeXT environment here). Apple has expanded on Services 10 fold in 10.5, and more and more developers are starting to take advantage of them. Sadly Services haven't been largely useable in Carbon applications, but 10.5 is making a turning point in that.

But back to the point at hand, I didn't have any issues with stability in even the beta versions of Mac OS X I was given to critique. Usually it was other factors at play that left me dissatisfied in one way or another.

Now, can someone FUBAR a Mac OS X system? Absolutely! And Macs that are open to many users under the administration of inexperienced admins are perfect examples of this... But then again, Windows systems under the same conditions are just as bad (which is why you'll never see me using the disingenuous tactic of holding a Windows system in a computer lab up as an example of their general stability).

As for 10.3 specifically... it is still being used by a majority of my clients (and I have it on three of my systems) without any issues what so ever. The only problems I've seen came from people attempting to run applications designed for 10.4 in 10.3... but I saw the same issues with people attempting to run apps designed for 10.3 in 10.2. Otherwise those have been absolutely rock solid releases. My clients encountered more issues with 10.5.0/10.5.1 than they had with the releases of 10.2, 10.3 and 10.4 combined. But 10.5 was a pretty big change.

All lemons should be this bad...

Last edited:

My philosophy has been if it ain't broke, don't fix it. If you aren't feeling a need, stay with what works.This machine's on 10.4(.11) and it's been rock solid for years. I hadn't thought about upgrading it for this reason. Are there any reasons why I should?

Some applications don't transition well (like earlier versions of Adobe's Creative Suite). You should always keep that in the back of your mind before a move like that.

Last edited:

A

Amaris

Guest

3.) I used a few Macs on occasion at school. For one video project, I had no choice but to use the Mac since the PC's available at the time weren't up to the challenge. The Mac crashed on me at least 12 times in that project. The first three crashes happened while ripping the raw footage to the computer, all within an hour. Not good.

Oddly, school Macs always seem to have significantly more problems than personal Macs. Probably due to the larger volume of users (and admins!) who don't know what they're doing.

Or at least that was true back in the OS9 days. I suspect OSX is a bit more "foolproof".

That Power Mac G5 was running the latest version OSX avaialble at the time. This was 2006 so, I think it was 10.5.3. Which is that, Panther?

10.5 is Leopard (2007).

10.4 is Tiger (2005)

10.3 is Panther (2003)

J.

This machine's on 10.4(.11) and it's been rock solid for years. I hadn't thought about upgrading it for this reason. Are there any reasons why I should?

Keep in mind that if you're on a PowerPC machine, moving to 10.5 will end Classic support. I don't see any reason to take a PowerPC machine past 10.4.

Developers who want to use Objective-C 2.0 need 10.5.I don't see any reason to take a PowerPC machine past 10.4.

Developers who want to use Objective-C 2.0 need 10.5.I don't see any reason to take a PowerPC machine past 10.4.

Any developer still working on a PowerPC machine has some unusual goals in mind....

Insuring backwards compatibility?Any developer still working on a PowerPC machine has some unusual goals in mind....

Besides, it's only been, what, two and a half years since the Mac Pros debuted? While the large developers have probably migrated their devs by now, hobbyists and smaller companies could well be on the same machines as they were back then. It's a PC, but I know that my dev machine at work is probably at least five years old.

Besides, it's only been, what, two and a half years since the Mac Pros debuted? While the large developers have probably migrated their devs by now, hobbyists and smaller companies could well be on the same machines as they were back then. It's a PC, but I know that my dev machine at work is probably at least five years old.Really? Link?Most of that I read on Wikipedia ages ago.

Wikipedia's Apple, NeXT and Rhapsody pages are painfully deficient. I've found tons of errors throughout. One of my favorite ones was their original description of the Darwin version numbering system. Finally someone in another forum just replaced it whole by quoting me (that page's history here, the thread is here... I go by RacerX there). But if you believe that you got that same info from Wikipedia, I'd be interested in seeing where it is. Because between ages ago and recently they haven't had a good track record on this subject in my book.

Sadly most of the people tending those Wikipedia pages know little and were definitely not there first hand for most of what happen. For example (as long as we are on the subject) the entry for TextEdit has it as first featured in NeXT's NEXTSTEP and OPENSTEP... but it was actually first introduced as a demo app in OPENSTEP and was never part of NEXTSTEP. The default word processor for both NEXTSTEP and OPENSTEP was Edit... which replaced WriteNow (whose entry also states that TextEdit was what replaced it). These errors start adding up and get compounded... and in this case all one had to do was actually use NEXTSTEP to know this.

A

Amaris

Guest

That's quite the history lesson, Shaw. Most of that I read on Wikipedia ages ago. Apple is interesting but, the cost is too high for me. I do like my iPod Touch, though. That is the coolest little prize I've ever won in any competition.

Buy used or refurbished and save 60% off the cost.

J.

Well, my Mac arrived today and I have to say that this is the neatest machine I've used! I LOVE THIS. I'm muddling my way around (real programmers don't read the manual) and so far I'm pleased. I just need to figure out how I will move my Windows files to this machine and I'll be set.

Well, my Mac arrived today and I have to say that this is the neatest machine I've used! I LOVE THIS. I'm muddling my way around (real programmers don't read the manual) and so far I'm pleased. I just need to figure out how I will move my Windows files to this machine and I'll be set.

Apple has a page explaining it:

http://www.apple.com/support/switch101/migrate/

(real programmers don't read the manual)

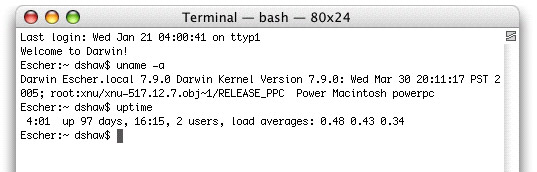

Well, they do, but only in the form of man pages accessed from the unix terminal.

A

Amaris

Guest

Well, my Mac arrived today and I have to say that this is the neatest machine I've used! I LOVE THIS. I'm muddling my way around (real programmers don't read the manual) and so far I'm pleased. I just need to figure out how I will move my Windows files to this machine and I'll be set.

Someone after my own heart.

J.

If you are not already a member then please register an account and join in the discussion!