According to

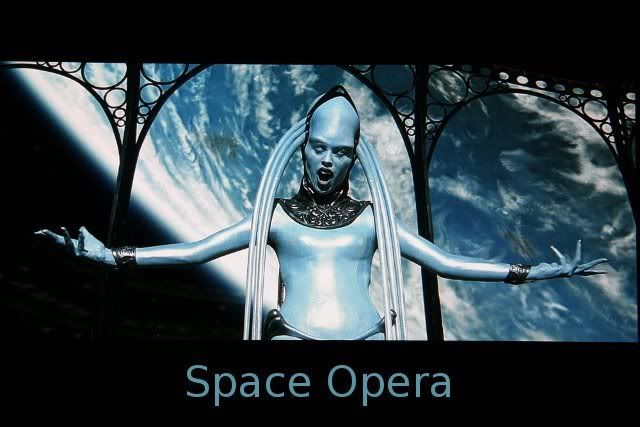

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_opera, Hartwell, David G. and Kathryn Cramer [in

The Space Opera Renaissance; Tor Books, 2006; ISBN 0-76530-617-4] define space opera as a sub-genre of science fiction. In other words, by that definition, all space opera is science fiction. Other sub-genres of science fiction would include hard, soft, cyberpunk, etc.

I used to classify

Star Wars as something other than science fiction ["science fantasy" is what the magazine

Starlog classified it as in the late 1970's]. But now I agree with both

stj and

Kegg in this quote.

PS Star Wars is science fiction because it throws in an energy field from a biological phenomenon instead of saying "GOD."

As far as the science goes Star Wars is science fiction because the Death Star is a moon-sized mobile space platform that destroys planets and is all done by

science. If the entirety of Star Wars had some word swaps to set it in say, a medevial environment, the Death Star would still be a huge scientific contraption and thus at least qualify it as a kind of steampunk setting.

The problem with trying to come up with some sort of restrictive, ivory tower definition of sf is that, invariably, it will bear no resemblance to how the term is actually used in the real world. Any definition of science fiction that excludes STAR WARS, for instance, is only going to make sense to purists.

This is true, but I'd add to it the observation that anyone who tries to define science fiction as somehow exclusively about plausible science or realistic predictions of the future (or anything else fairly serious) will also exclude a lot of well regarded sci-fi literature - most all of Dick's books don't really fit into this allegedly

serious sci-fi definiton, for example. Asimov's Galactic Roman Space Empire doesn't get in either and I can't see a place for that planet with giant sandworms. And so on.

Basically you either let the people with laserswords in, or you're left pretty exclusively with hard sci-fi, a slice so narrow as to be meaningless.

I agree with everyone in this quote,

stj,

Kegg, and

Greg Cox.

Why did I change my mind, and learn to love the b--I mean, learn to love

Star Wars as science fiction? In part for what

Kegg said at the end about letting "the people with laserswords in" and in part for what

Greg Cox said. I began to accept that the reason for excluding things from the genre was simply on the grounds that they were not "serious enough".

That's when I focused on two questions. First, if one is going to admit any fictitious science into science fiction, then just how plausible must the science be? It turns out that, except in cases that are actually known to represent impossibilities, "plausible fictitious science" is a nonsensical term. The reasons are as follows.

In the first place, only real science ever could be truly plausible. Anything else will always run up against situations where it is contradicted (at least I have no reason to doubt this proposition, at this time). In the second place, scientific theories are by their very nature

refutable, which means that they may strictly speaking be proven false, and found to be in need of either revision or rethinking, should experimental evidence indicate that this is so. So, even actual scientific theories [i.e. real science] cannot be proven to be free from implausibilities. Therefore, it cannot logically be faulted to postulate something that cannot be (or that hasn't yet been) disproven. Furthermore, formally assessing the likelihood of such a thing is really mathematically very problematic and could not in practice be rigorously done except in trivial and uninteresting cases. It is at this point that one sees that the distinction between plausible and implausible fictitious science is arbitrary. The only logically meaningful distinction is between the possible and the impossible, where by "possible" we mean simply not having been proven impossible. Real science falls into the realm of the possible, but so does anything else speculative [for which no proof of impossibility yet exists].

It is furthermore at this point that more interesting, and incidentally literary, considerations rise to the fore as means of subjectively grading works that all share a broad and inclusive genre. One should be willing to accept certain seeming implausibilities if there is a payoff in terms of moral lesson, education, characterization, entertainment value, or anything else that one finds personally engaging.

And so at this point, the second question suggests itself. What sorts of fiction should be admitted that develops stories in terms of science? This question really answers itself, though: as many kinds of stories as are in fiction itself.

) but stylistically not at all. Style matters.

) but stylistically not at all. Style matters.